Note: This post originally called Showers’ system Classical Dispensationalism. This was incorrect; his system is Revised Dispensationalism (though some do not see this distinction and would label him Traditional Dispensational).

Having grown up Dispensational, I recently began to examine Covenantal theology and compare it to Dispensationalism. I was given a copy of Showers’ book There Really Is A Difference: A Comparison of Covenant and Dispensational Theology to read. My copy is the eighth printing from 2002, copyright 1990.

This post began as a review on Amazon but I quickly realized I could not reasonably fit it into a product review format and decided to post it here instead.

The Review

This book does seem to me to be a faithful exposition of Revised (Traditional) Dispensational theology. Showers lays out what are, to my knowledge, the best arguments for DT. His overview of the major eschatological views, while biased towards the Pre-Trib, Pre-Mill position, are moderately helpful for someone largely unfamiliar with other positions.

However, I cannot recommend this book. I will lay out several of my reasons roughly in the order they occur in the book.

Extra-Biblical Arguments

First, Showers begins his discussion by positing 6 “necessary elements of a valid exposition of the biblical philosophy of history (2)”. He gives no defense and little explanation of these elements. Whether or not you agree with his elements, any attempt to systematize the Bible should begin with the Bible, not with an undefended list of requirements.

His list of “necessary elements” is as follows:

For an exposition to be valid…

1 – It must contain an ultimate purpose or goal for history toward the fulfillment of which all history moves….

2 – It must recognize distinctions or things that differ in history….

3 – It must have a proper concept of the progress of revelation…. (2-5) [numbering and formatting added]

He ends his comments on element 3 with, in my opinion, an additional requirement; “it must not make the earlier revelation say all that the later revelation said” (5).

4 – It must have a unifying principle which ties the distinctions and progressive stages of revelation together and directs them toward the fulfillment of the purpose of history….

5 – It must give a valid explanation of why things have happened the way they have, why things are the way they are today, and where things are going in the future….

6 – It must offer appropriate answers to man’s three basic questions: Where have we come from? Why are we here? Where are we going? (Showers 5-6) [numbering and formatting added]

While all these are problematic to some degree (if only because Showers gives no defense of them), I will only interact with one.

Regarding element 5, while I am not entirely certain what Showers means by this point, he does say

An exposition of the biblical philosophy of history must be able to explain how, when, and why such things as murder, false religions, capital punishment, human government, different languages, different nations, anti-Semitism, Roman Catholicism, Islam, the Renaissance, and the Reformation began. Why did the Holocaust of World War II happen? Why is there a modern state of Israel in existence? Why is the present Middle East crisis taking place? (6)

As he is explicitly discussing biblical philosophy of history, I take him to mean more than simply being able to list the sequence of events that lead to, for instance, World War II and the Holocaust. For example, I understand him to mean, rather than simply being able to explain “because of the strict reparations agreement forced on Germany following WWI, in addition to the economic downturn during the ’30s, Germans were deeply dissatisfied with their economic and political state. This provided an opportunity for Hitler to come to power…” but rather to be able to to explain (for instance) “Because of God’s promises to Abraham and his descendants as well as the Jews’ continued rejection of their Messiah, God allowed the Holocaust in order to both drive the Jews back to Him and to begin the reformation of the nation of Israel in the land promised to the Jews.”

If I am correct in my understanding of Showers’ requirement here, then this point is highly problematic because it directly attacks the transcendence of God. It essentially asks us to claim to be able to know the mind of God on matters where He has not told us His mind. You might say I am being too harsh here but Showers does not say “it must be able to suggest how, when, and why…” but rather “it must be able to explain how, when, and why…” This is asking for a claim of certainty, not of a claim of possibility. (This idea, of being able to ascertain why God allows a particular event or series of events to occur, is, in my experience, widely held among Dispensational Christians in the united States of America.)

Misquotation

Secondly, in addition to the problematic list of “necessary elements”, in his explanation of Covenant Theology, Showers misquotes Louis Berkhof. Showers states

Covenant Theology did not begin as a system until the 16th and 17th centuries. It did not exist in the early Church. Louis Berkhof, a prominent Covenant Theologian, wrote “In the early Church Fathers the covenant idea is not found at all.” Nor was the system developed during the Middle Ages or by the prominent Reformers Luther, Calvin, Zwingli, or Melanchthon. (7)

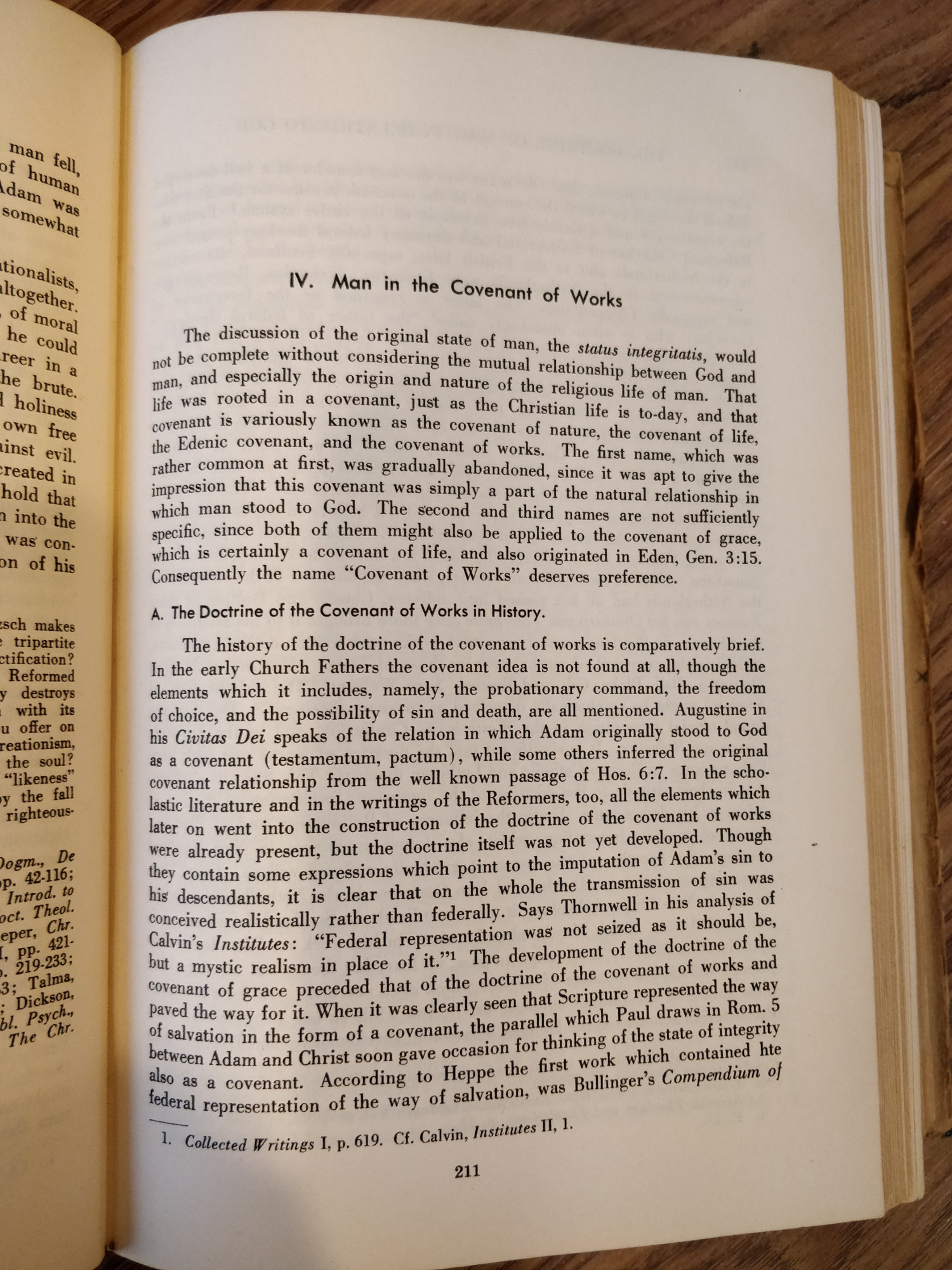

There are two separate problems with this quotation. First, Berkhof does not end his sentence where Showers ends it. The full sentence is “In the early Church Fathers the covenant idea is not found at all, though the elements which it includes, namely, the probationary command, the freedom of choice, and the possibility of sin and death, are all mentioned” (211). This remainder of the sentence weakens Showers point, but does not directly contradict it. But the second problem is that Berkhof is not even talking about Covenant Theology here! He is discussing the Covenant of Works. In context, the quote is

The history of the doctrine of the covenant of works is comparatively brief. In the early Church Fathers the covenant idea is not found at all, though the elements which it includes, namely, the probationary command, the freedom of choice, and the possibility of sin and death, are all mentioned. (Berkhof 211)

While I don’t know Showers’ thoughts, I don’t believe he could have mistakenly misquoted Berkhof here. I have included a picture of the source for this quotation as evidence that even a cursory glance at the quoted section makes it obvious that Berkhof was discussing a particular covenant and not Covenant Theology more broadly. In my opinion, this apparent dishonesty is enough by itself to discount the entire book.

Limited Understanding of Covenant Theology

This next section could be developed into several separate points but, to shorten this review, I’ve treated them as one.

Throughout the book, in his dealings with Covenant Theology, Showers only ever discusses the Paedo-baptist understanding of CT. This is most clearly seen in his chapter “An Examination of Covenant Theology.” In this chapter, he includes fifty-one references; all but eight of them are from Louis Berkhof’s Systematic Theology. Of the remaining eight, two are from Ryrie (a Dispensationalist), and the remaining six are from four other Covenant Theologians. Of the forty-five references from Covenant Theologians, one is from a Baptist. In short, Showers draws his understanding of Covenant Theology overwhelmingly from Paedo-baptists and even there he draws almost entirely from Berkhof. Showers’ understanding of CT is not robust. (Note also that he quotes from Berkhof’s 1941 edition of Systematic Theology despite several later editions being available.)

Because Showers only focuses on Paedo-baptist CT, many (I would argue most) of his arguments against CT simply do not apply to Credo-baptist CT. Further, Showers primarily addresses only the Paedo-baptistic form of CT that sees no difference in substance between the Abrahamic and Mosaic Covenants. While he does at least acknowledge that some Covenantal Theologians see a substantial difference between the Abrahamic and Mosaic Covenants, he fails to interact with their particular form of CT and therefore several of his arguments do not apply to all of even the Paedo-baptist understandings of Covenant Theology.

Further Consequence of Limited Understanding

Probably due to his failure to properly understand Covenantal thought, Showers’ given “ultimate goal of history” for Covenant Theology and his discussion of it is suspect; he states that “Covenant Theology sees the ultimate goal of history as being the glory of God through the redemption of the elect” (20). While I do wonder if this is not too narrow (I believe most who hold to CT would simply say the ultimate goal of history is the glory of God), even with the goal as stated, Showers plays a word trick when he claims that goal is too narrow. He says

Although the redemption of elect human beings is a very important part of God’s purpose for history, it is only one part of that purpose. During the course of history, God not only has a program for the elect but also a program for the nonelect (Rom. 9:10-23). (20)

Showers then goes on to mention several other groups or individuals who are distinct from the elect. But there is no denial of differing plans for different groups in the goal as stated which simply says that the redemption of the elect is the ultimate goal of history. Saying that something is the ultimate goal implies that there are secondary goals.

Unfair Treatment

Fourthly, Showers is rather disingenuous with regards to his treatment of Dispensational Theology compared to his treatment of Covenant Theology. In his introduction of DT, he defines Dispensational Theology as “a system of theology which attempts to develop the Bible’s philosophy of history on the basis of the sovereign rule of God” (27). Compare this to his definition of Covenant Theology; “Covenant Theology can be defined very simply as a system of theology which attempts to develop the Bible’s philosophy of history on the basis of two or three covenants” (7).

If he were to define DT in the same manner as CT, he should say “Dispensational Theology can be defined as a system of theology which attempts to develop the Bible’s philosophy of history on the basis of several dispensations.” Also, Showers’ given definition of DT applies equally well to CT. There is nothing distinctly Dispensational about his definition.

Further, let’s compare Showers’ introduction to DT with his introduction to CT. Showers writes

Dispensational Theology did not exist as a developed system of thought in the early Church, although early Church leaders did recognize some of the biblical principles which are basic to Dispensational Theology. For example, Clement of Alexandria (150-220 A.D.) recognized four dispensations of God’s rule. Augustine noted the fact that God has employed several distinct ways of working in the world as He executes His plan for history. (27)

Now compare that to his introduction to CT.

Covenant Theology did not begin as a system until the 16th and 17th centuries. It did not exist in the early Church. Louis Berkhof, a prominent Covenant Theologian, wrote, “In the early Church Fathers the covenant idea is not found at all.” Nor was the system developed during the Middle Ages or by the prominent Reformers Luther, Calvin, Zwingli, or Melanchthon. (7)

Recall that neither Berkhof’s sentence nor thought ends where Showers cuts it off but rather continues.

In the early Church Fathers the covenant idea is not found at all, though the elements which it includes, namely, the probationary command, the freedom of choice, and the possibility of sin and death, are all mentioned. Augustine in his Civitas Dei speaks of the relation in which Adam originally stood to God as a covenant…, while some others inferred the original covenant relationship from the well known passages of Hos. 6:7. (Berkhof 211)

Showers excluded Berkhof’s discussion of the elements of that covenant that are found in the early Church. This is especially noteworthy as Showers’ discussion of early Church usage of Dispensational ideas closely parallels Berkhof’s statements. If he were being honest in his comparison, Showers would have mentioned places the “biblical principles” which are basic to Covenant Theology were recognized by the early Church leaders.

Finally under this point, while Showers ends his discussion of Covenant Theology with a chapter critiquing CT, there is no corresponding chapter or even section examining short-comings of the Dispensational system. Nowhere in the book does Showers even admit that Dispensational Theology has problems of its own. While it is expected that an author who holds to DT will believe and write that DT is a better system than CT, an honest comparison of the two requires that author to acknowledge the weaknesses of both.

Further Thoughts

I do not intend to critique Dispensational Theology in this review, only the book in question. The majority and remainder of There Really is a Difference is largely Showers’ exposition of the Dispensational system. As his explanation is consistent with other Revised Dispensational theologians, I only have a few things more to say.

As Showers repeats what I regard as two of the most serious failings of most forms of DT, I will briefly critique those specific parts of DT here. In discussing the Abrahamic Covenant, its promises, and the unconditional nature of the covenant, Showers says

If the Abrahamic Covenant is unconditional…, then every promise of that covenant must be fulfilled including the promises that Israel would be given forever the land described in Genesis 15:18 and that the Abrahamic Covenant would be an everlasting covenant for Israel. This would mean… that the Dispensational-Premillennial view of those prophecies is correct.

By contrast, if the Abrahamic Covenant is conditional… the Dispensational-Premillenial view of those prophecies would be wrong. (60) [emphasis original]

Also note Showers’ statements regarding the purpose of the Millenium.

Inasmuch as the seventh dispensation will be the final one, it will be characterized by the final fulfillment of the promises which God made to Abraham and his seed. Once promises are fulfilled, they cease to be promises. Thus, promise will no longer be a ruling factor in the last dispensation. (47)

And also his discussion of the end of the Millenium.

Man’s failure in conjunction with the seventh dispensation will bring God’s judgment…. In addition, God will crush the huge revolt which will take place immediately after the seventh dispensation by sending fire to destroy the human rebels and casting Satan into the lake of fire for everlasting torment (Rev. 20:9-10). (Showers 49)

Showers (in agreement with Revised Dispensational Theology) here claims that the everlasting promises made to Abraham and his seed are fulfilled in the seventh dispensation, the Millennium, which then ends with the final judgment. This is self-contradictory as the Millennium, according to Showers, is finite in time and ends with the final revolt and destruction of the world. Everlasting, eternal promises cannot be fulfilled within a 1000 year time period (see Showers p. 166), or any finite time period. Everlasting, eternal promises cannot “cease to be promises” or they are not everlasting and eternal. It is this Dispensational view, not the Covenantal view, that unbiblically limits the promises made to Abraham.

Secondly, Showers makes a rather large error here by claiming the Covenantal view teaches that the Abrahamic Covenant is conditional. While Showers correctly identifies an area of major disagreement between CT and DT (I would say it is the major area of disagreement), he incorrectly identifies the nature of the disagreement. Covenant Theology does not disagree with Dispensational Theology over the unconditional nature of the Abrahamic Covenant but over the recipients of the covenant, over who are the seed/offspring of Abraham. For evidence of this, see Pascal Denault’s discussion (found in The Distinctiveness of Baptist Covenant Theology, pp 105-116) of the difficulty the Paedo-baptist CT view has with the Mosaic Covenant precisely because it insists the Abrahamic Covenant must be unconditional. While I cannot claim to know that no Covenantal theologian has ever said the Abrahamic Covenant is conditional, that view is by no means normative.

Finally, at several points throughout his book, Showers uses strawman arguments when discussing a point. For example, when discussing the Church in the New Testament, Showers gives, as evidence that the Church did not exist in the Old Testament, several distinctions between Old Testament Israel and New Testament Church (184-186). No Covenant theologian has any issue with these distinctions because Covenant Theology does see distinctions between the people of God in the Old Testament and the people of God in the New Testament. Both Paedo and Credo-baptist Covenantal views hold that, with the coming of the New Covenant, the people of God (who either were OT Israel or within OT Israel, depending on the respective Covenantal view) were expanded to contain people from every nation, tribe, and tongue. Where CT and DT disagree is the nature of the distinction between the OT people of God and NT people of God, not the existence of the distinction.

Works Cited

Berkhof, Louis. Systematic Theology. Second Revised and Enlarged ed., Grand Rapids, WM. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1941.

Showers, Renald E. There Really is a Difference: A Comparison of Covenant and Dispensational Theology. 1990. Bellmawr, The Friends of Israel Gospel Ministry, Inc, 2002.

Good review. If you still have the book, I seem to remember a sentence in the introduction about two gospels – a bit of a conflict with Galatians 1.

Apologies for the slow reply; I was in the middle of a move & needed to upgrade the blog back-end.

I do still have the book. Showers says (3):

And Showers continues to discuss why he believes the two messages must have been “quite distinct.”

I don’t know for sure how Showers would respond to pointing out the conflict with Galatians 1, but I can guess that he probably would say “of course Paul condemns preaching any other gospel. We are in a different dispensation and the kingdom of heaven is no longer at hand but has been postponed. To preach it now would be to offer a false hope.”

Probably the best response to that, as well as to Showers entire argument that there are two gospels, is to point out first that just because the disciples preached the kingdom prior to understanding that Christ must suffer (he points to Matt 16:21 as proof they didn’t understand the “second” gospel until after preaching the “first”) doesn’t mean what they preached was different. After all, the OT prophets did not understand the extent of what they prophesied (1 Pet 1:10-12); why then would the disciples have to understand the extent of what they were preaching? And second that Paul equates preaching the kingdom with preaching Christ in Acts 20:20-21, 25. Further, Acts 28:23 & 31 both also tell us Paul preached the kingdom and Luke views this as involving preaching Jesus. This shows that preaching the kingdom is tantamount to preaching Christ crucified and, further, prevents the potential objection to Galatians 1 that I supposed would be the likely response.